Quantum Mechanics Is Different

The two-state system, also known as a bit, is the most fundamental classical system used in computer science. It serves as the fundamental unit of information, representing anything that has only two possible states, such as a coin that can be heads or tails, a switch that can be on or off, or a tiny magnet that is constrained to point north or south.

However, in the realm of quantum mechanics, the two-state system is referred to as a qubit, which is significantly more complex and interesting. Due to the incredibly small size of the objects studied in quantum mechanics, our human senses are not equipped to visualize them. Instead, we must rely on mathematical abstractions to understand the behavior of subatomic particles such as electrons.

The qubit allows for a much greater range of possibilities than its classical counterpart, the bit. While a bit can only exist in one of two states, a qubit can exist in a superposition of both states at once. This phenomenon, known as quantum superposition, allows for vastly greater computational power and opens up new possibilities in the fields of computer science and information technology.

1. How quantum mechanics is different:

- Different Abstractions. Quantum abstractions are fundamentally different from classical ones.

- States and Measurements. In the classical world, the relationship between the state of a system and the result of a measurement on that system is very straightforward. The labels that describe a state (the position and momentum of a particle, for example) are the same labels that characterize measurements of that state. To put it another way, one can perform an experiment to determine the state of a system. In the quantum world, this is not true. States and measurements are two different things, and the relationship between them is subtle and nonintuitive.

2. Spins and Qubits

The concept of spin, derived from particle physics, is another crucial aspect of quantum mechanics. Particles have properties in addition to their location in space. For example, they may or may not have electric charge or mass. Attached to the electron is an extra degree of freedom called its spin.

While the spin can be pictured naively as a little arrow pointing in some direction, that classical picture is too simplistic to accurately represent the real situation. Instead, the quantum spin, isolated from the electron that carries it through space, is both the simplest and the most quantum of systems.

The isolated quantum spin is an example of the general class of simple systems we call qubits—quantum bits that play the same role in the quantum world as logical bits play in defining the state of your computer.

3. An Experiment

We began by discussing a very simple deterministic system: a coin that can show either heads (H) or tails (T). We can call this a two-state system, or a bit, with the two states being H and T. More formally we invent a “degree of freedom” called that can take on two values, namely +1 and −1. The state H is replaced by \(\sigma = +1\) and the state T by \(\sigma = -1\)

Classically, that’s all there is to the space of states. The system is either in state \(\sigma = +1\) or \(\sigma = -1\) and there is nothing in between. In quantum mechanics, we’ll think of this system as a qubit.

3.1. Evolution Law

We now discussed simple evolution laws in quantum world. The simplest law is just that nothing happens. In that case, if we go from one discrete instant (n) to the next (n + 1), the law of evolution is

\[\mathcal \sigma(n+1) = \sigma(n) \tag{1.1}\]3.2. New assumption

An experiment involves more than just a system to study. It also involves an apparatus A to make measurements and record the results of the measurements.

In the case of the two-state system, the apparatus interacts with the system (the spin) and records the value of \(\sigma\).

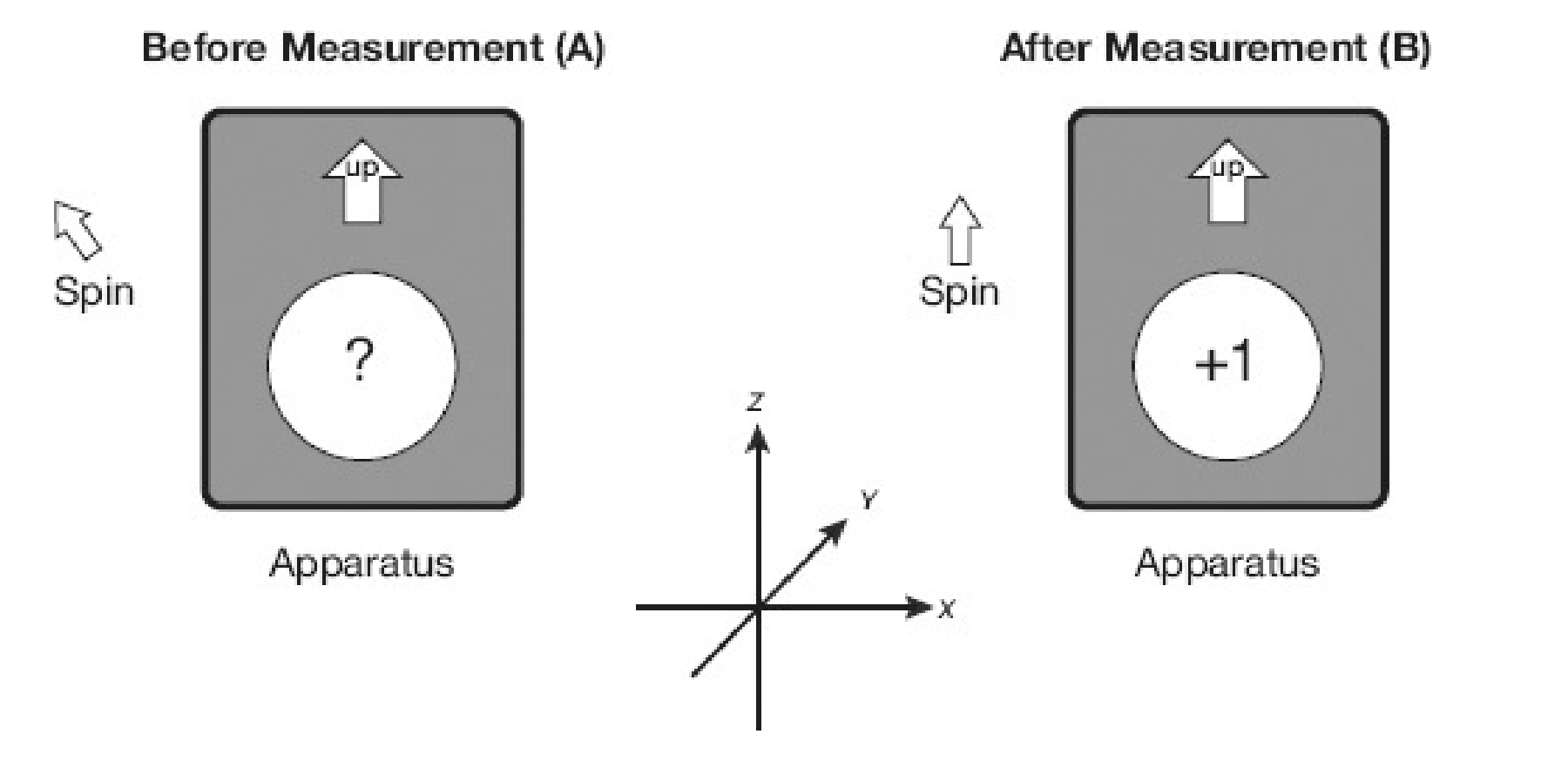

Think of the apparatus as a black box with a window that displays the result of a measurement. There is also a “this end up” arrow on the apparatus. The up-arrow is important because it shows how the apparatus is oriented in space, and its direction will affect the outcomes of our measurements. We begin by pointing it along the z axis (Fig. below).

Initially, we have no knowledge of whether \(\sigma = +1\) or \(\sigma = -1\) . Our purpose is to do an experiment to find out the value of \(\sigma\) .

Before the apparatus interacts with the spin, the window is blank. After it measures , the window shows a +1 or a −1. By looking at the apparatus, we determine the value of \(\sigma\).

The spin is now prepared in the \(\sigma_{z} = +1\) state. If the spin is not disturbed and the apparatus keeps the same orientation, all subsequent measurements will give the same result.

Now that we’ve measured \(\sigma\) , let’s reset the apparatus to neutral and, without disturbing the spin, measure \(\sigma\) again. Assuming the simple law, we should get the same asnwer as we did the first time. The result \(\sigma_{z} = +1\) will be followed by \(\sigma_{z} = +1\) . Likewise for \(\sigma_{z} = -1\). The same will be true for any number of repetitions. This is important because it allows us to confirm the result of an experiment. So far, there is no difference between classical and quantum physics.

From these results, we might conclude that is a degree of freedom that is associated with a sense of direction in space. If \(\sigma\) were an oriented vector of some sort, then it would be natural to expect that turning the apparatus over would reverse the reading.

If we are convinced that the spin is a vector, we would naturally describe it by three components: \(\sigma_{z}\), \(\sigma_{y}\), \(\sigma_{x}\). When the apparatus is upright along the z axis, it is positioned to measure \(\sigma_{z}\).

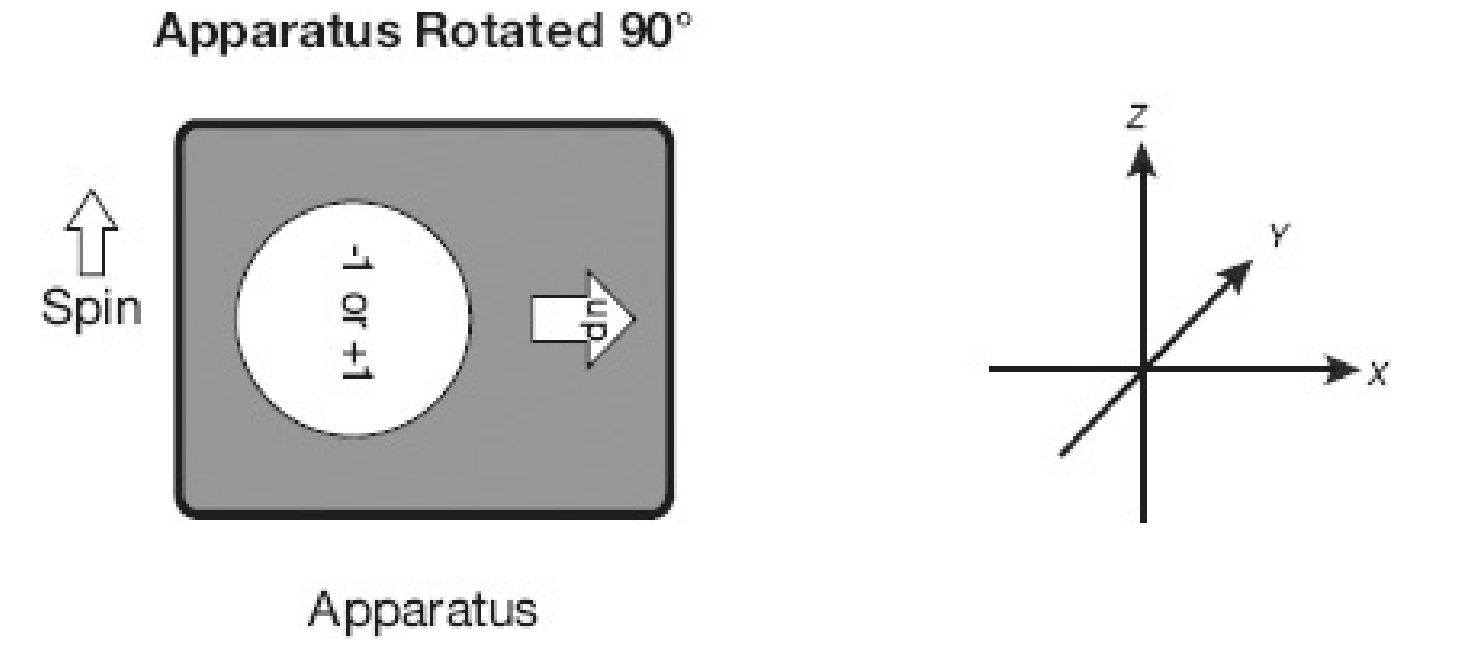

So far, there is still no difference between classical physics and quantum physics. The difference only becomes apparent when we rotate the apparatus through an arbitrary angle, say \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) radians (90 degrees).(Figure below)

The apparatus begins in the upright position (with the up-arrow along the z axis). A spin is prepared with \(\sigma = +1\). Next, rotate \(A\) so that the up-arrow points along the \(x\) axis, and then make a measurement of what is presumably the \(x\) component of the spin, \(\sigma_{x}\).

If in fact \(\sigma\) really represents the component of a vector along the up-arrow, one would expect to get zero. Initially, we confirmed that \(\sigma\) was directed along the \(z\) axis, suggesting that its component along \(x\) must be zero.

But we get a surprise when we measure \(\sigma_{x}\): Instead of giving \(\sigma_{x}=0\), the apparatus gives either \(\sigma_{x}=+1\) or \(\sigma_{x}=-1\). If the spin really is a vector, it is a very peculiar one indeed.

Nevertheless, we do find something interesting. Suppose we repeat the operation many times, each time following the same procedure, that is:

- Beginning with A along the z axis, prepare \(\sigma=+1\).

- Rotate the apparatus so that it is oriented along the \(x\) axis.

- Measure \(\sigma\).

The repeated experiment spits out a random series of plus-ones and minus-ones. Determinism has broken down, but in a particular way. If we do many repetitions, we will find that the numbers of events \(\sigma=+1\) and events \(\sigma=-1\) are statistically equal. In other words, the average value of is zero.

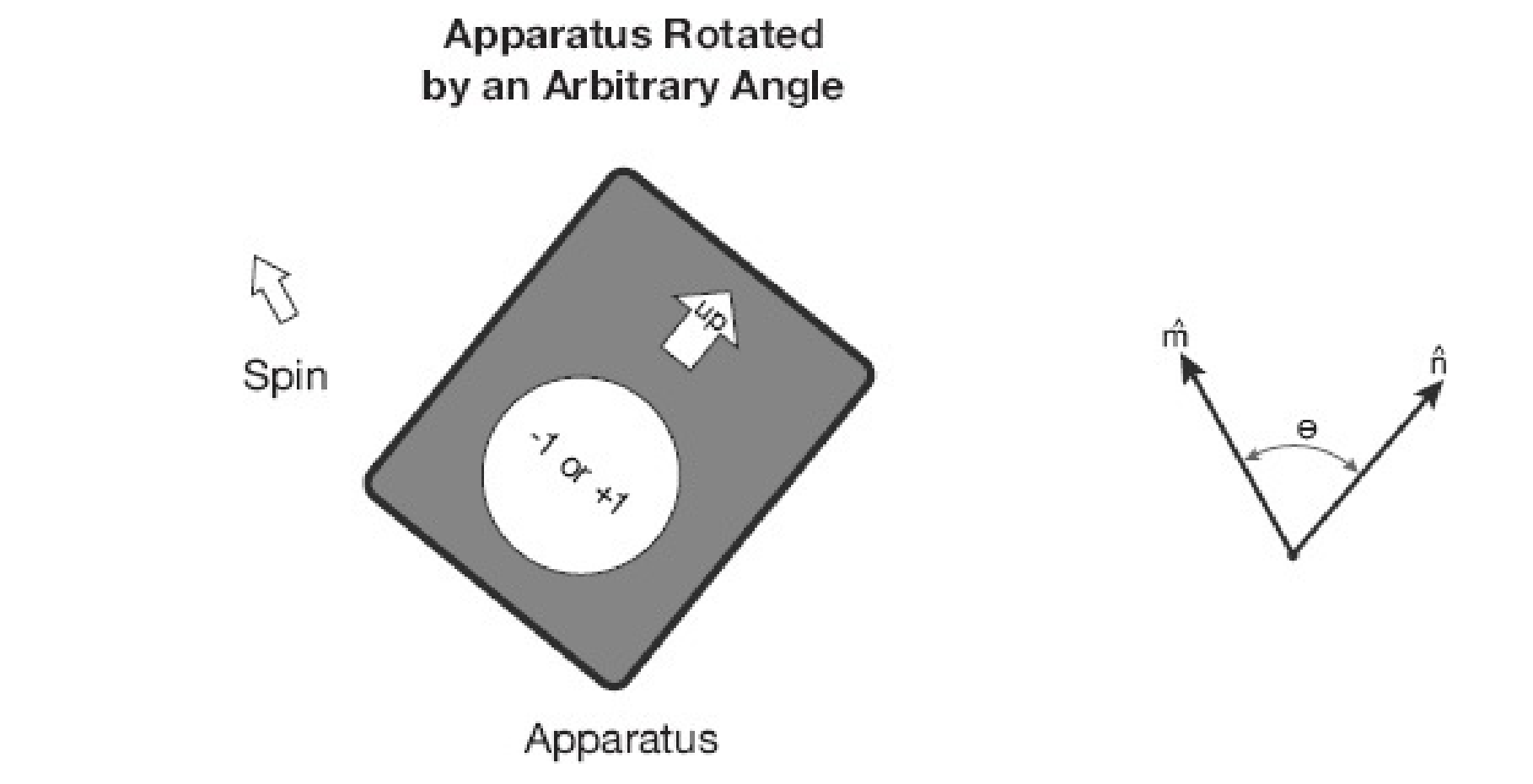

Now let’s do the whole thing over again, but instead of rotating \(A\) to lie on the \(x\) axis, rotate it to an arbitrary direction along the unit vector \(n\). Classically, if \(\sigma\) were a vector, we would expect the result of the experiment to be the component \(\sigma\) of along the \(n\) axis. If \(n\) lies at an angle \(\theta\) with respect to \(z\), the classical answer would be \(\sigma= cos\theta\) . But as you might guess, each time we do the experiment we get \(\sigma=+1\) or \(\sigma=-1\). However, the result is statistically biased so that the average value is \(cos\theta\). In other words, the average will be \(n \dot m\).

The quantum mechanical notation for the statistical average of a quantity \(Q\) is Dirac’s bracket notation \(\langle Q\rangle\). We may summarize the results of our experimental investigation as follows: If we begin with \(\boldsymbol{A}\) oriented along \(\widehat{m}\) and confirm that \(\sigma=+1\), then subsequent measurement with \(A\) oriented along \(\widehat{n}\) gives the statistical result \(\langle\sigma\rangle=\widehat{n} \cdot \widehat{m} \tag{2}\)

4. Summary

What we are learning is that quantum mechanical systems are not deterministic—the results of experiments can be statistically random—but if we repeat an experiment many times, average quantities can follow the expectations of classical physics, at least up to a point.

Reference:

1. Nielsen, Michael A., and Isaac Chuang. "Quantum computation and quantum information." (2002): 558-559.

2. Asfaw, Abraham, et al. "Learn quantum computation using qiskit." Accessed: Oct 24 (2020): 2020.

3. Susskind, Leonard, and Art Friedman. Quantum mechanics: the theoretical minimum. Basic Books, 2014.