In this section, we will discuss the mathematical background knowledge about quantum computing.

1. Complex Numbers

A complex number z is the sum of a real number and an imaginary number. We can write it as

\[z=x+i y\]

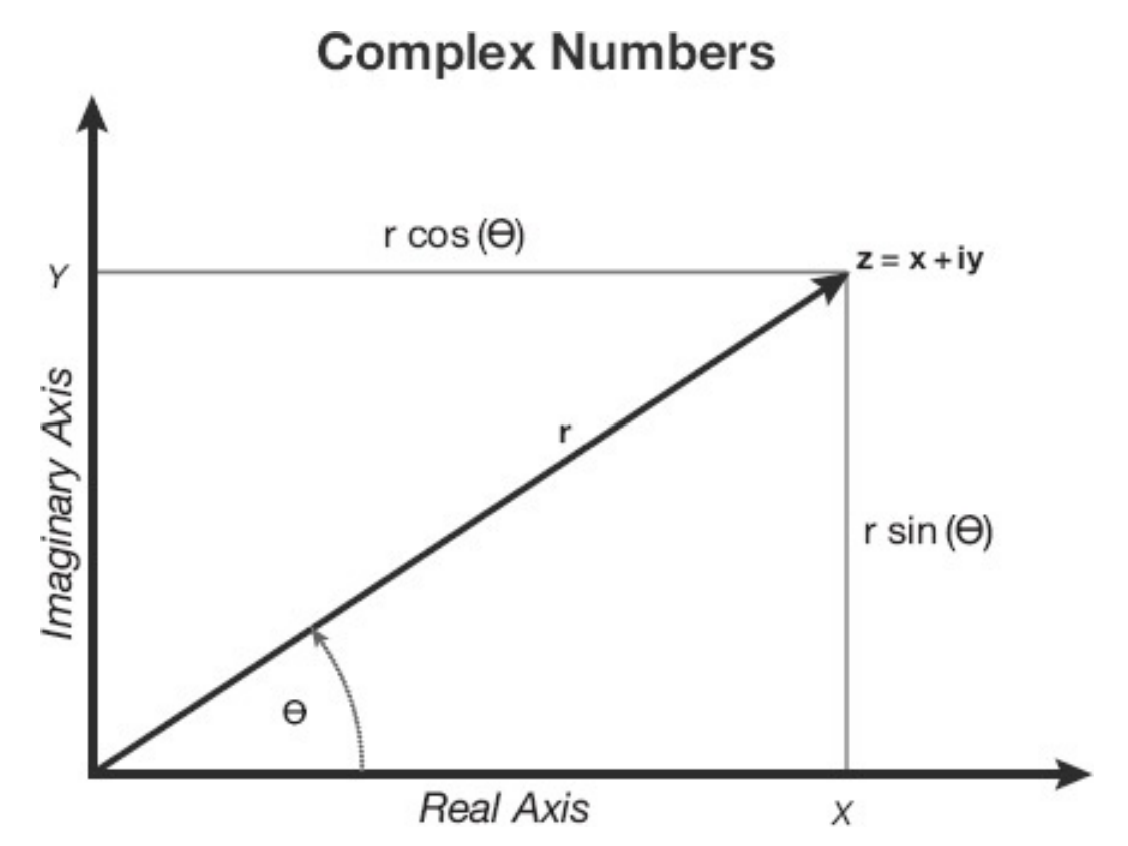

Two Common Ways to Represent Complex Numbers. In the Cartesian representation, x and y are the horizontal (real) and vertical (imaginary) components. In the polar representation, r is the radius, \($\theta\) and is the angle made with the x axis. In each case, it takes two real numbers to represent a single complex number.

where \(x\) and \(y\) are real and \(i^{2}=-1\) . Complex numbers can be added, multiplied, and divided by the standard rules of arithmetic. They can be visualized as points on the complex plane with coordinates \(x, y\) . They can also be represented in polar coordinates:

\[z=r e^{i \theta}=r(\cos \theta+i \sin \theta) .\]Adding complex numbers is easy in component form: just add the components. Similarly, multiplying them is easy in their polar form: Simply multiply the radii and add the angles:

\[\left(r_{1} e^{i \theta_{1}}\right)\left(r_{2} e^{i \theta_{2}}\right)=\left(r_{1} r_{2}\right) e^{i\left(\theta_{1}+\theta_{2}\right)}\]Every complex number \(z\) has a complex conjugate \(z^{*}\) that is obtained by simply reversing the sign of the imaginary part. If

\[z=x+i y=r e^{i \theta}\]then

\[z^{*}=x-i y=r e^{-i \theta}\]Multiplying a complex number and its conjugate always gives a positive real result:

\[z^{*} z=r^{2}\]It is of course true that every complex conjugate is itself a complex number, but it’s often helpful to think of \(z\) and \(z^{*}\) as belonging to separate “dual” number systems.

Dual here means that for every \(z\) there is a unique \(z^{*}\) and vice versa.

There is a special class of complex numbers that I’ll call “phase-factors.” A phase-factor is simply a complex number whose \(r\)-component is 1 . If \(z\) is a phase-factor, then the following hold:

\[\begin{gathered} z^{*} z=1 \\ z=e^{i \theta} \\ z=\cos \theta+i \sin \theta \end{gathered}\]2. Vector Space

The space of states of a quantum system is not a mathematical set;6 it is a vector space. Relations between the elements of a vector space are different from those between the elements of a set, and the logic of propositions is different as well.

The vector spaces we use to define quantum mechanical states are called Hilbert spaces. When you come across the term Hilbert space in quantum mechanics, it refers to the space of states. A Hilbert space may have either a finite or an infinite number of dimensions.

In quantum mechanics, a vector space is composed of elements called ket-vectors or just kets.

In quantum mechanics, a vector space is composed of elements \(\vert A\rangle\) called ket-vectors or just kets. Here are the axioms we will use to define the vector space of states of a quantum system ( \(z\) and \(w\) are complex numbers):

- The sum of any two ket-vectors is also a ket-vector:

- Vector addition is commutative:

- Vector addition is associative:

- There is a unique vector 0 such that when you add it to any ket, it gives the same ket back:

- Given any ket \(\vert A\rangle\) , there is a unique ket \(-\vert A\rangle\) such that

- Given any ket \(\vert A\rangle\) and any complex number \(z\) , you can multiply them to get a new ket. Also, multiplication by a scalar is linear:

- The distributive property holds:

Axioms 6 and 7 taken together are often called linearity. Axiom 6 allows a vector to be multiplied by any complex number.

3. Bras and Kets

As we have seen, the complex numbers have a dual version: in the form of complex conjugate numbers. In the same way, a complex vector space has a dual version that is essentially the complex conjugate vector space. For every ket-vector \(\vert A\rangle\) , there is a “bra” vector in the dual space, denoted by \(\langle A\vert\) . Why the strange terms bra and ket Shortly, we will define inner products of bras and kets, using expressions like \(\langle B \vert A\rangle\) to form bra-kets or brackets. Inner products are extremely important in the mathematical machinery of quantum mechanics, and for characterizing vector spaces in general.

Bra vectors satisfy the same axioms as the ket-vectors, but there are two things to keep in mind about the correspondence between kets and bras:

- Suppose \(\langle A\vert\) is the bra corresponding to the ket \(\vert A\rangle\) , and \(\langle B\vert\) is the bra corresponding to the ket \(\vert B\rangle\) . Then the bra corresponding to

is

\[\langle A\vert +\langle B\vert\]- If \(z\) is a complex number, then it is not true that the bra corresponding to \(z\vert A\rangle\) is \(\langle A\vert z\) . You have to remember to complexconjugate. Thus, the bra corresponding to

is

\[\langle A\vert z^{*}\]In the concrete example where kets are represented by column vectors, the dual bras are represented by row vectors, with the entries being drawn from the complex conjugate numbers. Thus, if the ket \(\vert A\rangle\) is represented by the column

\[\left(\begin{array}{l} \alpha_{1} \\ \alpha_{2} \\ \alpha_{3} \\ \alpha_{4} \\ \alpha_{5} \end{array}\right)\]then the corresponding bra \(\langle A\vert\) is represented by the row

\[\left(\begin{array}{lllll} \alpha_{1}^{*} & \alpha_{2}^{*} & \alpha_{3}^{*} & \alpha_{4}^{*} & \alpha_{5}^{*} \end{array}\right)\]4. Inner Product

The analogous operation for bras and kets is the inner product. The inner product is always the product of a bra and a ket and it is written this way: \(\langle B \vert A\rangle\) The result of this operation is a complex number. The axioms for inner products are not too hard to guess:

- They are linear: \(\langle C\vert \{\vert A\rangle+\vert B\rangle\}=\langle C \vert A\rangle+\langle C \vert B\rangle\)

- Interchanging bras and kets corresponds to complex conjugation: \(\langle B \vert A\rangle=\langle A \vert B\rangle^{*} \text {. }\)

In the concrete representation of bras and kets by row and column vectors, the inner product is defined in terms of components:

\[\begin{aligned} \langle B \vert A\rangle &=\left(\begin{array}{lllll} \beta_{1}^{*} & \beta_{2}^{*} & \beta_{3}^{*} & \beta_{4}^{*} & \beta_{5}^{*} \end{array}\right)\left(\begin{array}{c} \alpha_{1} \\ \alpha_{2} \\ \alpha_{3} \\ \alpha_{4} \\ \alpha_{5} \end{array}\right) \\ &=\beta_{1}^{*} \alpha_{1}+\beta_{2}^{*} \alpha_{2}+\beta_{3}^{*} \alpha_{3}+\beta_{4}^{*} \alpha_{4}+\beta_{5}^{*} \alpha_{5} \end{aligned}\]The rule for inner products is essentially the same as for dot products: add the products of corresponding components of the vectors whose inner product is being calculated.

- Normalized Vector: A vector is said to be normalized if its inner product with itself is 1 . Normalized vectors satisfy,

- Orthogonal Vectors: Two vectors are said to be orthogonal if their inner product is zero. \(\vert A\rangle\) and \(\vert B\rangle\) are orthogonal if

5. Orthogonal Basis

Obviously, there is nothing special about the particular axes x, y, and z. As long as the basis vectors are of unit length and are mutually orthogonal, they comprise an orthonormal basis.

Let’s consider an N-dimensional space and a particular orthonormal basis

of ket-vectors labeled \(\vert i\rangle\) The label \(i\) runs from 1 to \(N\) . Consider a vector \(\vert A\rangle\) , written as a sum of basis vectors:

\[\vert A\rangle=\sum_{i} \alpha_{i}\vert i\rangle\]The \(\alpha_{i}\) are complex numbers called the components of the vector, and to calculate them we take the inner product of both sides with a basis bra \(\langle j\vert\) :

\[\langle j \vert A\rangle=\sum_{i} \alpha_{i}\langle j \vert i\rangle\]Next, we use the fact that the basis vectors are orthonormal. This implies that \(\langle j \vert i\rangle=0\) if \(i\) is not equal to \(j\) , and \(\langle j \vert i\rangle=1\) if \(i=j\) . In other words, \(\langle j \vert i\rangle=\delta_{i j}\) . This makes the sum in Eq. \(1.4\) collapse to one term:

\[\langle j \vert A\rangle=\alpha_{j}\]Thus, we see that the components of a vector are just its inner products with the basis vectors.

Reference:

1. Nielsen, Michael A., and Isaac Chuang. "Quantum computation and quantum information." (2002): 558-559.

2. Asfaw, Abraham, et al. "Learn quantum computation using qiskit." Accessed: Oct 24 (2020): 2020.

3. Susskind, Leonard, and Art Friedman. Quantum mechanics: the theoretical minimum. Basic Books, 2014.