HHL is the basis of many more advanced algorithms and is important in various applications such as machine learning and modelling quantum systems.

1. Linear System Problem and Overview of HHL Algorithm

A linear system problem (LSP) can be represented as the following

\[A \vec{x}=\vec{b}\]where \(A\) is an \(N_{b} \times N_{b}\) Hermitian matrix and \(\vec{x}\) and \(\vec{b}\) are \(N_{b}\)-dimensional vectors. For simplicity, it is assumed \(N_{b}=2^{n_{b}} . A\) and \(\vec{b}\) are known and \(\vec{x}\) is the unknown to be solved, i.e.

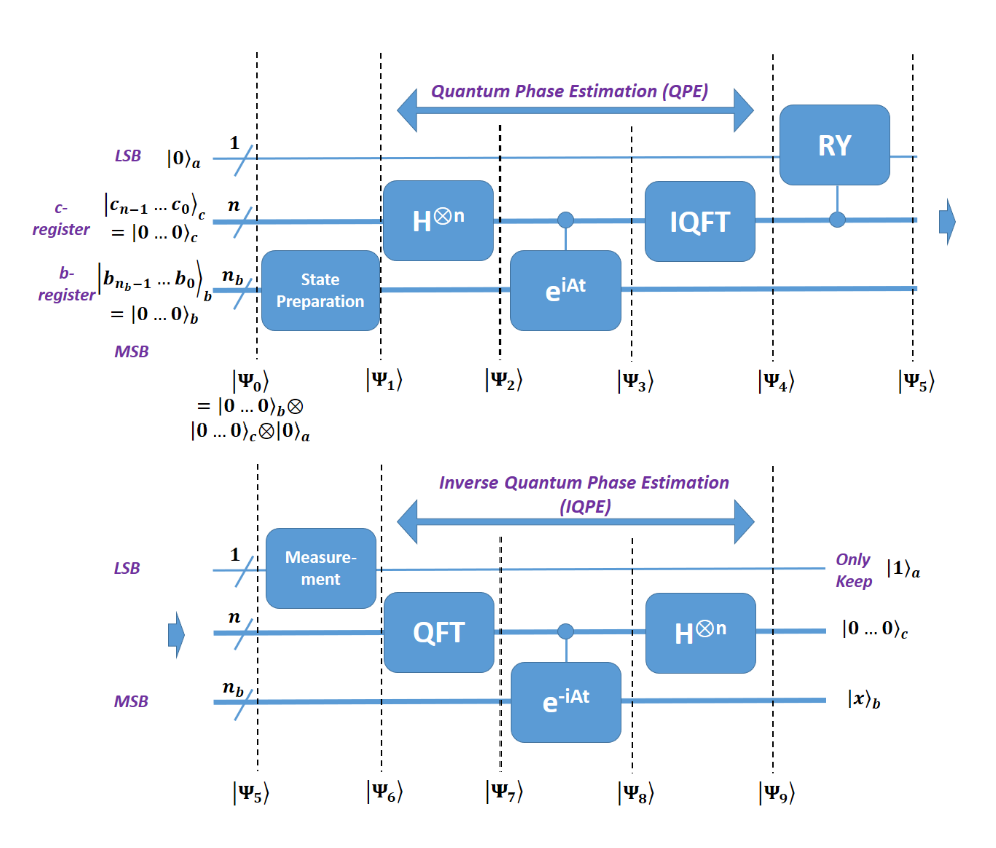

\[\vec{x}=A^{-1} \vec{b}\]Figure below shows the schematic of the HHL algorithm and the corresponding circuit. The HHL algorithm has 5 main components, namely state preparation, quantum phase estimation (QPE), ancilla bit rotation, inverse quantum phase estimation (IQPE), and measurement.

The clock qubits are used to store the encoded eigenvalues of A, and larger n results in higher accuracy when the encoding is not exact.

The matrix \(A\), which is a Hamiltonian, may be written as a linear combination of its eigenvectors, \(\left\vert u_{i}\right\rangle\) weighted by its eigenvalues, \(\lambda_{i}\).

\[A=\sum_{i=0}^{2^{n_{b}-1}} \lambda_{i}\left\vert u_{i}\right\rangle\left\langle u_{i}\right\vert\]Since \(\mathrm{A}\) is diagonal in its eigenvector basis, its inverse is simply, \(A^{-1}=\sum_{i=0}^{2^{n} b-1} \lambda_{i}^{-1}\left\vert u_{i}\right\rangle\left\langle u_{i}\right\vert\). \(\vec{b}\) can be also expressed in the basis of \(\mathrm{A}\), such that

\[\vert b\rangle=\sum_{j=0}^{2^{n} b-1} b_{j}\left\vert u_{j}\right\rangle\]Therefore, it can be encoded as,

\[\vert x\rangle=A^{-1}\vert b\rangle=\sum_{i=0}^{2^{n_{b}-1}} \lambda_{i}^{-1} b_{i}\left\vert u_{i}\right\rangle\]by using the fact that \(\left\langle u_{i} \mid u_{j}\right\rangle=\delta_{i j}\). The goal of the HHL algorithm is to find the solution in this form and \(\vert x\rangle\) is stored in the b-register.

2. State Preparation

There are total \(n_{b}+n+1\) qubits, and they are initialized as:

\[\left\vert \Psi_{0}\right\rangle=\vert 0 \cdots 0\rangle_{b}\vert 0 \cdots 0\rangle_{c}\vert 0\rangle_{a}=\vert 0\rangle^{\otimes n_{b}}\vert 0\rangle^{\otimes n}\vert 0\rangle\]In the state preparation, \(\vert 0 \cdots 0\rangle_{b}\) in the b-register needs to be rotated to have the amplitudes correspond to the coefficients of \(\vec{b}\). That is

\[\vec{b}=\left(\begin{array}{c} \beta_{0} \\ \beta_{1} \\ \vdots \\ \beta_{N_{b}-1} \end{array}\right) \Leftrightarrow \beta_{0}\vert 0\rangle+\beta_{1}\vert 1\rangle+\cdots+\beta_{N_{b}-1}\left\vert N_{b}-1\right\rangle=\vert b\rangle\]The vector \(\vec{b}\) is represented in a column form on the left with coefficients \(\beta^{\prime} s\), which is also a valid representation of \(\vert b\rangle\). On the right, the corresponding basis of the Hilbert space formed by the \(n_{b}\) qubits is written explicitly. Therefore,

\[\left\vert \Psi_{1}\right\rangle=\vert b\rangle_{b}\vert 0 \cdots 0\rangle_{c}\vert 0\rangle_{a}\]From now on, some of the subscripts of the kets will be omitted when there is no ambiguity. Since the state preparation depends on the actual value of \(\vec{b}\), it will be discussed in more detail in the numerical example.

3. Phase Estimation

Quantum phase estimation (QPE) is also an eigenvalue estimation algorithm. QPE has three components, namely the superposition of the clock qubits through Hadamard gates, controlled rotation, and Inverse Quantum Fourier Transform (IQFT). Here we assume the readers are already familiar with IQFT and it will not be explained in detail. In the first step where a superposition of the clock qubits is created, Hadamard gates are applied to the clock qubits to obtain,

\[\begin{aligned} \left\vert \Psi_{2}\right\rangle &=I^{\otimes n_{b}} \otimes H^{\otimes n} \otimes I\left\vert \Psi_{1}\right\rangle \\ &=\vert b\rangle \frac{1}{2^{\frac{n}{2}}}(\vert 0\rangle+\vert 1\rangle)^{\otimes n}\vert 0\rangle \end{aligned}\]

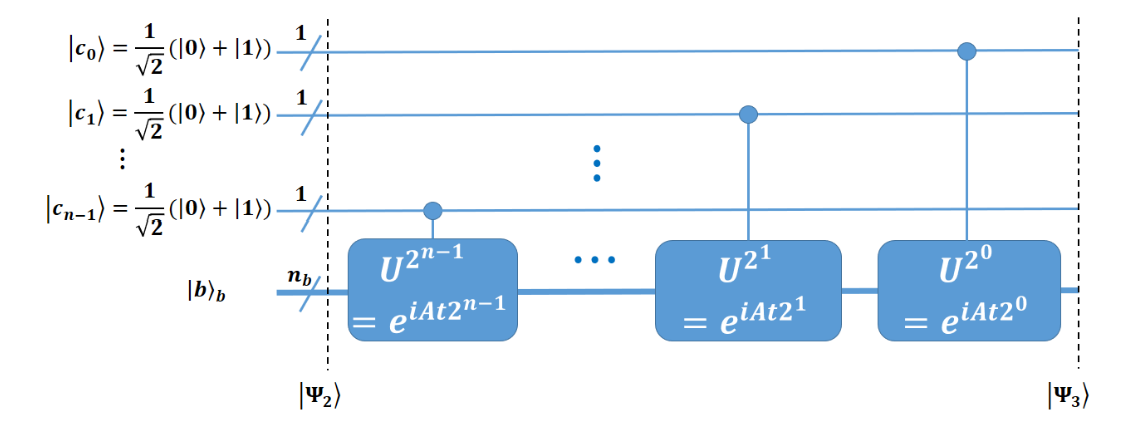

In the controlled rotation part, \(U\) is applied to \(\vert b\rangle\) with the clock qubits as the control qubits (Figure 2). For simplicity, we begin by assuming that \(\vert b\rangle\) is an eigenvector of \(U\) with eigenvalue \(e^{2 \pi i \phi}\). Therefore

\[U\vert b\rangle=e^{2 \pi i \phi}\vert b\rangle\]When the control clock qubit is \(\vert 0\rangle,\vert b\rangle\) will not be affected. If the clock bit is \(\vert 1\rangle, U\) will be applied to \(\vert b\rangle\). This is equivalent to multiplying \(e^{2 \pi i \phi 2^{i}}\) in front of the \(\vert 1\rangle\) of the \(i-t h\) clock qubit. Therefore, after the controlled- \(U\) operation, we have

\[\begin{aligned} \left\vert \Psi_{3}\right\rangle &=\vert b\rangle \otimes\left(\frac{1}{2^{\frac{n}{2}}}\left(\vert 0\rangle+e^{2 \pi i \phi 2^{n-1}}\vert 1\rangle\right) \otimes\left(\vert 0\rangle+e^{2 \pi i \phi 2^{n-2}}\vert 1\rangle\right) \otimes \cdots \otimes\left(\vert 0\rangle+e^{2 \pi i \phi 2^{0}}\vert 1\rangle\right)\right) \otimes\vert 0\rangle_{a} \\ &=\vert b\rangle \frac{1}{2^{\frac{n}{2}}} \sum_{k=0}^{2^{n}-1} e^{2 \pi i \phi k}\vert k\rangle\vert 0\rangle_{a} \end{aligned}\]In the IQFT part, only the clock qubits are affected. Note that in certain literature, this is called Quantum Fourier Transform (QFT).

\[\begin{aligned} \left\vert \Psi_{4}\right\rangle &=\vert b\rangle \operatorname{IQFT}\left(\frac{1}{2^{\frac{n}{2}}} \sum_{k=0}^{2^{n}-1} e^{2 \pi i \phi k}\vert k\rangle\right)\vert 0\rangle_{a} \\ &=\vert b\rangle \frac{1}{2^{\frac{n}{2}}} \sum_{k=0}^{2^{n}-1} e^{2 \pi i \phi k}(I Q F T\vert k\rangle)\vert 0\rangle_{a} \\ &=\vert b\rangle \frac{1}{2^{n}} \sum_{k=0}^{2^{n}-1} e^{2 \pi i \phi k}\left(\sum_{y=0}^{2^{n}-1} e^{-2 \pi i y k / N}\vert y\rangle\right)\vert 0\rangle_{a} \\ &=\frac{1}{2^{n}}\vert b\rangle \sum_{y=0}^{2^{n}-1} \sum_{k=0}^{2^{n}-1} e^{2 \pi i k(\phi-y / N)}\vert y\rangle\vert 0\rangle_{a} \end{aligned}\]Due to interference, only for \(\vert y\rangle\) satisfying the condition \(\phi-y / N=0\) will have a finite amplitude of \(\sum_{k=0}^{2^{n}-1} e^{0}=2^{n}\). Otherwise, the amplitude is \(\sum_{k=0}^{2^{n}-1} e^{2 \pi i k(\phi-y / N)}=0\) due to destructive interference. By ignoring the states with zero amplitude, we may rewirte \(\left\vert \Psi_{4}\right\rangle\) as

\[\left\vert \Psi_{4}\right\rangle=\vert b\rangle\vert N \phi\rangle\vert 0\rangle_{a}\]Therefore, in QPE, the clock qubits are used to represent the phase information of \(U\), which is \(\phi\), and the accuracy depends on the number of qubits, \(n\). In Hamiltonian encoding, \(U\) is related to \(A\) through

\[U=e^{i A t}\]where \(t\) is the evolution time for that Hamiltonian. \(U\) is obviously also diagonal in \(A^{\prime} s\) eigenvector, \(\left\vert u_{i}\right\rangle\), basis. If \(\vert b\rangle=\left\vert u_{j}\right\rangle\),

\[U\vert b\rangle=e^{i \lambda_{j} t}\left\vert u_{j}\right\rangle\]By equating \(i \lambda_{j} t\) to \(2 \pi i \phi\) in Eq. (11), we get \(\phi=\lambda_{j} t / 2 \pi\) and Eq. (14) becomes

\[\left\vert \Psi_{4}\right\rangle=\left\vert u_{j}\right\rangle\left\vert N \lambda_{j} t / 2 \pi\right\rangle\vert 0\rangle_{a}\]Thus the eigenvalues of \(A\) have been encodeded in the clock qubits (basis encoding). However, in general, \(\vert b\rangle=\sum_{j=0}^{2^{n} b-1} b_{j}\left\vert u_{j}\right\rangle\) (Eq. 4), by using superposition,

\[\left\vert \Psi_{4}\right\rangle=\sum_{j=0}^{2^{n_{b}-1}} b_{j}\left\vert u_{j}\right\rangle\left\vert N \lambda_{j} t / 2 \pi\right\rangle\vert 0\rangle_{a}\]\(\lambda_{j}\) are usually not integers. We will choose \(t\) so that \(\tilde{\lambda}_{j}=N \lambda_{j} t / 2 \pi\)

are integers. Therefore, the encoded values \(\tilde{\lambda}_{j}\)

can be different from \(\lambda_{j} . \Psi_{4}\)

can be rewritten as

\[\left\vert \Psi_{4}\right\rangle=\sum_{j=0}^{2^{n_{b}-1}} b_{j}\left\vert u_{j}\right\rangle\left\vert \tilde{\lambda}_{j}\right\rangle\vert 0\rangle_{a}\]4. Controlled Rotation and Measurement of the Ancilla Qubit

The next step is to rotate the ancilla qubit, \(\vert 0\rangle_{a}\), based on the encoded eigenvalues in the c-register, such that

\[\left\vert \Psi_{5}\right\rangle=\sum_{j=0}^{2^{n_{b}-1}} b_{j}\left\vert u_{j}\right\rangle\left\vert \tilde{\lambda_{j}}\right\rangle\left(\sqrt{1-\frac{C^{2}}{\tilde{\lambda_{j}}^{2}}}\vert 0\rangle_{a}+\frac{C}{\tilde{\lambda_{j}}}\vert 1\rangle_{a}\right)\]where \(C\) is a constant. When the ancilla qubit is measured, the ancilla qubit wavefunction will collapse to either \(\vert 0\rangle\) or \(\vert 1\rangle\). If it is \(\vert 0\rangle\), the result will be discarded and the computation will be repeated until the measurement is \(\vert 1\rangle\). Therefore, the final wavefunction of interest is

\[\left\vert \Psi_{6}\right\rangle=\frac{1}{\sqrt{\sum_{j=0}^{2^{n} b-1}\left\vert \frac{b_{j} C}{\lambda_{j}}\right\vert ^{2}}} \sum_{j=0}^{2^{n} b-1} b_{j}\left\vert u_{j}\right\rangle\left\vert \tilde{\lambda}_{j}\right\rangle \frac{C}{\tilde{\lambda_{j}}}\vert 1\rangle_{a}\]where the prefactor is due to normalization after measurement. Since \(\left\vert \frac{C}{\lambda_{j}}\right\vert ^{2}\) is the probably of obtaining \(\vert 1\rangle\) when the ancilla bit is measured, \(C\) should be chosen to be as large as possible. Compared to Eq. (5), the result resembles the answer \(\vert x\rangle\) that we are looking for. However, it is entangled with the clock qubits, \(\left\vert \tilde{\lambda}_{j}\right\rangle\). This means that we cannot factorize the result into a tensor product of the c-register and b-register. Therefore, we need to uncompute the state to unentangle them.

The measurement can be and is usually performed after uncomputation. However, since the ancilla bit is not involved in any operations after the controlled rotation, measuring the ancilla bit before the uncomputation gives the same result. For simplicity in the derivation, it is thus performed before the uncomputation.

5. Uncomputation - Inverse QPE

Firstly, QFT is applied to the clock qubits.

\[\left\vert \Psi_{7}\right\rangle=\frac{1}{\sqrt{\sum_{j=0}^{2^{n_{-}-1}}\left\vert \frac{b_{\frac{b}{\lambda}} C_{1}}{\lambda_{1}}\right\vert ^{2}}} \sum_{j=0}^{2 m_{b}-1} \frac{b_{j} C}{\hat{\lambda}_{j}}\left\vert u_{j}\right\rangle Q F T\left\vert \hat{\lambda_{j}}\right\rangle\vert 1\rangle_{a}\]Then inverse controlled-rotations of the b-register by the clock qubits are applied with \(U^{-1}=e^{-i A t}\). Similar to the forward process, when the control clock qubit is \(\vert 0\rangle,\left\vert u_{j}\right\rangle\) will not be affected. If the clock bit is \(\vert 1\rangle, U^{-1}\) will be applied to \(\left\vert u_{j}\right\rangle\). This is equivalent to multiplying \(e^{-i \lambda_{j} t}\) in front of the \(\vert 1\rangle\) of the \(i-t h\) clock bit. Therefore,

\[\left\vert \Psi_{8}\right\rangle=\frac{1}{2^{n / 2} \sqrt{\sum_{j-0}^{2 n-1}\left\vert \frac{b_{2} C}{\lambda_{j}}\right\vert ^{2}}} \sum_{j=0}^{2^{n b-1}} \frac{b_{j} C}{\overline{\lambda_{j}}}\left\vert u_{j}\right\rangle\left(e^{-i \lambda_{j} t} \sum_{j=0}^{2^{n}-1} e^{2 \pi i y \lambda_{j} / N}\vert y\rangle\right)\vert 1\rangle_{a}\]Since we have set \(\bar{\lambda}_{j}=N \lambda_{j} t / 2 \pi\)

, therefore, the two exponential terms cancel each other and

\[\begin{aligned} \left\vert \Psi_{s}\right\rangle &=\frac{1}{2^{n / 2} \sqrt{\sum_{j=0}^{2^{n-1}}\left\vert \frac{b_{j} C}{\lambda_{j}}\right\vert ^{2}}} \sum_{j=0}^{2^{n_{0}-1}} \frac{b_{j} C}{\lambda_{j}}\left\vert u_{j}\right\rangle \sum_{y=0}^{2^{n}-1}\vert y\rangle\vert 1\rangle_{a} \\ &=\frac{1}{2^{n / 2} \frac{N t}{2 x} \sqrt{\sum_{j=0}^{2 n_{b}-1}\left\vert \frac{b_{j} C}{\lambda_{j}}\right\vert ^{2}}} \sum_{j=0}^{2^{n_{3}-1}} \frac{b_{j} C}{\lambda_{j}}\left\vert u_{j}\right\rangle \sum_{j=0}^{2^{n}-1}\vert y\rangle\vert 1\rangle_{a} \\ &=\frac{C}{2^{n / 2} \sqrt{\sum_{j-0}^{2^{n b}-1}\left\vert \frac{b_{j} C}{\lambda_{j}}\right\vert ^{2}}}\vert x\rangle \sum_{y=0}^{2^{n}-1}\vert y\rangle\vert 1\rangle_{a} \end{aligned}\]The clock qubits and the b-register are now unentangled, and the b-register stores \(\vert x\rangle\). By applying the Hadamard gate on the clock qubits, finally, we have

\[\begin{aligned} \left\vert \Psi_{9}\right\rangle &=\frac{1}{\sqrt{\sum_{j=0}^{2^{n} b-1}\left\vert \frac{b_{j} C}{\lambda_{j}}\right\vert ^{2}}} \sum_{j=0}^{2^{m b}-1} \frac{b_{j} C}{\lambda_{j}}\left\vert u_{j}\right\rangle\vert 0\rangle^{\beta n}\vert 1\rangle_{a} \\ &=\frac{1}{\sqrt{\sum_{j=0}^{2^{2 n}-1}\left\vert \frac{b_{j} C}{\lambda_{j}}\right\vert ^{2}}}\vert x\rangle_{b}\vert 0\rangle_{c}^{\beta n}\vert 1\rangle_{a} \end{aligned}\]6. Example

For example, take \(N=2\),

\[A=\left(\begin{array}{cc} 1 & -1 / 3 \\ -1 / 3 & 1 \end{array}\right), \quad \vec{x}=\left(\begin{array}{l} x_{1} \\ x_{2} \end{array}\right) \quad \text { and } \quad \vec{b}=\left(\begin{array}{l} 1 \\ 0 \end{array}\right)\]Then the problem can also be written as find \(x_{1}, x_{2} \in \mathbb{C}\) such that

\[\left\{\begin{array}{l} x_{1}-\frac{x_{2}}{3}=1 \\ -\frac{x_{1}}{3}+x_{2}=0 \end{array}\right.\]The eigenvectors of A are, respectively,

\[\left\vert u_{1}\right\rangle=\left(\begin{array}{c} 1 \\ -1 \end{array}\right) \quad \text { and } \quad\left\vert u_{2}\right\rangle=\left(\begin{array}{l} 1 \\ 1 \end{array}\right)\]The eigenvalues of them are, \(\lambda_{1}=2 / 3 \quad \text { and } \quad \lambda_{2}=4 / 3\)

.

2 qubits are needed by encoding \(\lambda_{1}\) and \(\lambda_{2}\) as \(\vert01\rangle\) \(\vert10\rangle\) so that it maintains the ratio of e1/e0 = 2

it maintains the ratio of \(e_{1} / e_{0}=2 .\) This means \(\tilde{\lambda}_{0}=1\)

and \(\tilde{\lambda}_{1}=2\)

or in other words, \(\ket{\tilde{\lambda_{0}}}=\ket{ 01}\)

and \(\ket{ \tilde{\lambda_{1}}}=\vert 10\rangle\)

. This gives a perfect encoding with \(n=2(\) i.e. \(N=4)\). Therefore, \(t\) is chosen to be \(\frac{3 \pi}{4}\)

to achieve the encoding scheme since \(\tilde{\lambda}_{j}=N \lambda_{j} t / 2 \pi\)

.

On outcome 1 when measuring the auxiliary qubit, the state is

\[\frac{\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}} \ket{00}\ket{u_{1}} \frac{1}{2}\ket{ 1}+\frac{1}{\sqrt{2}}\ket{ 00}\ket{u_{2}} \frac{1}{4}\ket{ 1}}{\sqrt{5 / 32}}\]A quick calculation shows that

\[\frac{\frac{1}{2 \sqrt{2}}\ket{u_{1}}+\frac{1}{4 \sqrt{2}}\ket{u_{2}}}{\sqrt{5 / 32}}=\frac{\ket{ x}}{\vert \vert x \vert \vert }\]Since \(\vec{b}\) is a 2-dimensional complex vector, it can be encoded using 1 qubit and, thus, \(n_{b}=1\).

We can use \(\ket{u_{1}}\) and \(\ket{u_{2}}\) to find what is x.

The solution to the LSP is found to be

\[\vec{x}=\left(\begin{array}{c} \frac{3}{8} \\ \frac{9}{8} \end{array}\right)\]whereby, the ratio of \(\left\vert x_{0}\right\vert ^{2} \text { to }\left\vert x_{1}\right\vert ^{2} \text { is } 1: 9\)

.

7. Qiskit Version of HHL

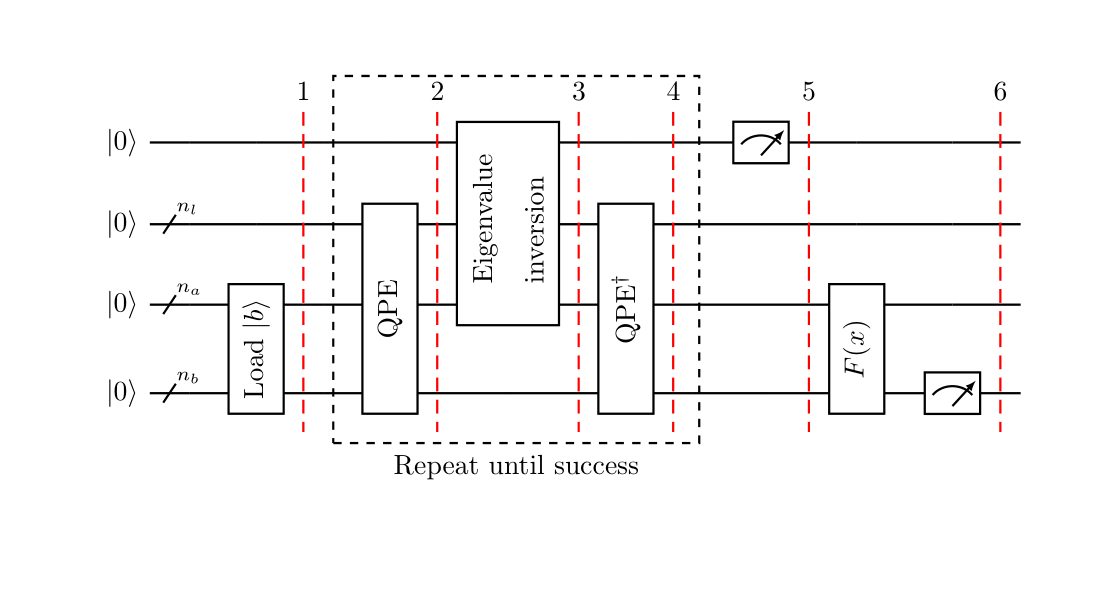

Qiskit’s implementation of HHL has slight differences with the above. The following part introduces HHL’s implementation and finds the differences.

The following figure shows the overall circuit.

The algorithm goes as the following:

- Load the data \(\ket{b} \in \mathbb{C}^{N}\). That is, perform the transformation

- Apply Quantum Phase Estimation (QPE) with

The quantum state of the register expressed in the eigenbasis of \(A\) is now \(\sum_{j=0}^{N-1} b_{j} \ket{\lambda_{j}}_{n l}\ket{u_{j}}_{n_{b}}\) where \(\ket{\lambda_{j}}_{n l}\) is the \(n_{l}\)-bit binary representation of \(\lambda_{j}\).

- Add an auxiliary qubit and apply a rotation conditioned on \(\ket{\lambda_{j}}\),

where \(C\) is a normalisation constant, and, as expressed in the current form above, should be less than the smallest eigenvalue \(\lambda_{\min }\) in magnitude, i.e., \(\vert C \vert <\lambda_{\min }\).

-

Apply \(\mathrm{QPE}^{\dagger}\). Ignoring possible errors from QQE, this results in \(\sum_{j=0}^{N-1} b_{j}\ket{0}_{n_{l}}\ket{u_{j}}_{n_{b}} (\sqrt{1-\frac{C^{2}}{\lambda_{j}^{2}}}\ket{0}+\frac{C}{\lambda_{j}}\ket{1})\)

-

Measure the auxiliary qubit in the computational basis. If the outcome is 1 , the register is in the post-measurement state

which up to a normalisation factor corresponds to the solution.

- Apply an observable \(M\) to calculate \(F(x):=\bra{x} M \ket{x}\).

Reference:

1. Nielsen, Michael A., and Isaac Chuang. "Quantum computation and quantum information." (2002): 558-559.

2. Asfaw, Abraham, et al. "Learn quantum computation using qiskit." Accessed: Oct 24 (2020): 2020.

3. Susskind, Leonard, and Art Friedman. Quantum mechanics: the theoretical minimum. Basic Books, 2014.

4. Morrell Jr, Hector Jose, and Hiu Yung Wong. "Step-by-Step HHL Algorithm Walkthrough to Enhance the Understanding of Critical Quantum Computing Concepts." arXiv preprint arXiv:2108.09004 (2021).