This is a collection of my notes on Econometrics. I will update this post as I progress. The notes are based on the lectures by Prof. Peng Wang in Hong Kong University of Science and Technology. I will not copy the content of the lectures directly. Instead, I will try to summarize the key points and add my own thoughts.

Topic 1: Linear Regression and Causal Inference

Regression Analysis of Causal Model

Causal effects can be identified by regression analysis.

- Assume the observed data is given by {Y_i, X_i, Z_i} for i = 1, …, n.

- The most simple causal model is the linear regression model:

- \[Y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_i + \epsilon_i\]

- \[\epsilon_i \sim N(0, \sigma^2)\]

- \(\beta_0, \beta_1\) are the parameters of the model.

- \(\epsilon_i\) is the error term.

This model can be motivated by the potential outcome framework. The model is a simplified version of the following model:

-

\[Y_i = Y_i(0) + [Y_i(1) - Y_i(0)] * 1{X_i = 1} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_i + \epsilon_i\]

- \(\beta_0 = E[Y_i(0)]\).

- \(\beta_1 = E[Y_i(1) - Y_i(0)]\).

- \(\epsilon_i = Y_i(0) - E[Y_i(0)]\).

- \(\epsilon\) includes the unobserved factors other than \(X_i\) that affect \(Y_i\).

-

if we run a regression of \(Y_i\) on \(X_i\), the estimator is biased by \epsilon_i, such a bias is called “omitted variable bias”. And unobserved factors other than \(X_i\) are called “confounders”.

- in OLS, let \(\{\beta_0, \beta_1\}\) be the true parameters of the model, and let \({\hat{\beta_0}, \hat{\beta_1}}\) be the OLS estimator.

- The estimator can be defined as \(\hat{\beta_1} = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n (Y_i - \bar{Y})(X_i - \bar{X})}{\sum_{i=1}^n (X_i - \bar{X})^2}\)

- if we have an iid sample, we then have the estimator as

\(\hat{\beta_1} = cov(Y, X) / var(X)\).

- iid: independent and identically distributed.

Unconfundedness

- Confounders: unobserved factors that are correlated with both the treatment. Ignoring them will cause “ommited variable bias”.

- However, if an unobserved factor is not correlated with the treatment, it is not a confounder, and ignoring it will not bias the estimate of the treatment effect.

- How to encounter confounders?

- Control variables

- Randomized experiments

- Instrumental variables

Ommited Variable Bias

- Method of Moments is a method to estimate the parameters of a model by matching the moments of the data to the moments of the model. \(cov(Y, X) = cov(\beta_0 + \beta_1 X + \epsilon, X) = \beta_1 cov(X, X) + cov(\epsilon, X)\)

- Then we can calculate the bias of the estimator: \(\hat{\beta_1} - \beta_1 = \frac{cov(\epsilon, X)}{var(X)}\)

- Ommited variable bias is defined as \(cov(\epsilon, X)/var(X)\), which is non-zero if \(X\) is correlated with \(\epsilon\).

- Example if X is a dummy variable, \(var(X) = p(1-p)\). Then \(cov(\epsilon, X) = E(\epsilon X) - E(\epsilon)E(X) = E(\epsilon X) - E(\epsilon) p = E(\epsilon X) - 0 = E(\epsilon X)\).

- We can use law of iterated expectation to get \(cov(\epsilon, X) = E\{E(\epsilon X \vert X)\} = E\{XE(\epsilon \vert X)\} = p \cdot E(\epsilon \vert X_i = 1)\).

- The ommited variable bias implies nonzero selection bias.

-

\[E{Y_i \vert X_i = 1} - E{Y_i \vert X_i = 0} = \beta_1 + E(\epsilon \vert X_i = 1) - E(\epsilon \vert X_i = 0)\]

- \(\beta_1\) is the causal effect. The second term is the selection bias variable bias.

- \(\epsilon_i = Y_i(0) - E[Y_i(0)]\).

- It also implies \(E\{Y_i(0)\vert X_i\} \neq E\{Y_i(0)\}\) or \(E\{Y_i(1)\vert X_i\} \neq E\{Y_i(1)\}\).

-

\[E{Y_i \vert X_i = 1} - E{Y_i \vert X_i = 0} = \beta_1 + E(\epsilon \vert X_i = 1) - E(\epsilon \vert X_i = 0)\]

Multiple Regression

- Multiple regression is a generalization of the simple regression model. Assume we have two regressors: \(Y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_{i} + \beta_2 W_i + \epsilon_i\)

- \(\beta_1\) reflects X’s direct effect on Y, when W remains the same.

Statistical theory of OLS

- Considering a linear regression model with \(p\) regressors: \(Y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_{i1} + \beta_2 X_{i2} + ... + \beta_p X_{ip} + \epsilon_i\)

- The four least squares assumptions:

- LSA1: The error term \(\epsilon_i\) is normally distributed with mean zero and constant variance \(\sigma^2\).

- LSA2: The error term \(\epsilon_i\) is uncorrelated with the regressors \(X_{ij}\).

- LSA3: finite 4th moments.

- LSA4: no perfect multicollinearity.

- In such case, the OLS estimators are unbiased and consistent and are asymptotically normal.

- Unbiased: \(E(\hat{\beta_j}) = \beta_j\)

- Consistent: \(\hat{\beta_j} \rightarrow \beta_j\)

- Asymptotically normal: \(\hat{\beta_j} \sim N(\beta_j, \sigma^2 / n)\)

- \(Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X + u\).

- \(\beta_1 = cov(Y, X) / var(X)\).

- \(cov(u, X) = 0\).

- \(Y = E(Y \vert X) + u\).

- \(cov(u, X) = 0\).

- \(E(u \vert X) = 0\).

- \(E(u^2 \vert X) = var(u \vert X)\).

- \(E(u^3 \vert X) = 0\).

- \(E(u^4 \vert X) = 3 var(u \vert X)^2\).

The causal diagram approach

- If the causal relation goes like this: \(X \rightarrow Y\) or \(W \rightarrow X \rightarrow Y\) or \(X \rightarrow W \rightarrow Y\), then we can use the causal diagram approach to estimate the causal effect of X on Y.

- If we have the causal model X both causes X and W, and W causes Y, which is like:

- \(X \rightarrow W \rightarrow Y\).

- \(X \rightarrow Y\).

In this case, we can not control for W, because X affects Y both through W and directly.

- Another special case goes like:

- \(X \rightarrow W\).

- \(W \rightarrow Y\).

In such case, Aading W in the regression will reduce the estimation precision. W is redunant regressor.

- If the causal relation goes like:

- \(X \rightarrow Y\).

- \(W \rightarrow X \rightarrow Y\).

In this case, we can control for W to get the causal effect of X on Y.

- If we have a case like, we should not control for X in the regression, because we will create spurious correlation between X and Y.

- \(X \rightarrow W\).

- \(X \rightarrow Y\).

- \(Y \rightarrow W\).

- How to decitewhether a variable is a good control variable?

- The variable blocks all spurious paths between X and Y.

- The variable is not affected by X.

The potential outcome framework

- The conditional mean independence assumption:

- \(E(Y_i \vert X_i, W_i) = E(Y_i \vert W_i)\), this implies \(Y_i\) is uncorrerlated with \(X_i\), given \(W_i\), equivalently, \(E(\epsilon_i \vert X_i, W_i) = E(\epsilon_i \vert W_i)\).

- independence \(\rightarrow\) constant conditional mean \(\rightarrow\) no correlation.

- no correlation \(\not\Rightarrow\) constant conditional mean \(\not\Rightarrow\) independence.

Bad Controls using potential outcome anaylsis

Consider two observed dummies: \(W_i = 1\) if white collar, \(X_i = 1\) if college graduate.

- Potential earnings \(\{Y_{1i}, Y_{0i}\}\); potential white-collar status \(\{W_{1i}, W_{0i}\}\).

- Observed outcomes vs potential (linked by observed treatment): \(Y_i = X_iY_{1i} + (1-X_i)Y_{0i}\), \(W_i = X_iW_{1i} + (1-X_i)W_{0i}\).

- To simplify analysis, assume that \(X\) is randomly assigned and thus is independent of all potential outcomes \(\{Y_{1i}, Y_{0i}, W_{1i}, W_{0i}\}\).

- Suppose we hold constant \(W_i=1\): only look at earning difference in the white-collar group due to college.

- Selection bias = \(E[Y_{0i}\vert W_{1i}=1] - E[Y_{0i}\vert W_{0i}=1] < 0\): those whose lower potential job is white collar despite no college should have higher earnings anyway.

- So comparing earnings difference among white-collar group tends to underestimate the effect of college on earnings. The potential outcomes analysis verifies both the causal diagram’s implications and our economic intuition.

Counterfactual Estimation

A treatment was assignmned to a random sample of individuals, and the outcome \(Y_i\) is observed for each individual. The goal is to estimate the causal effect of the treatment on the outcome.

- The treatment \(D_i\) is a binary variable, \(D_i = 1\) if the individual is treated, \(D_i = 0\) if the individual is not treated.

- The randomness is conditional on the observed covariates \(X_i\).

1. Prove that the counterfactual \(E(Y_i(0) \vert D_i = 1)\) can be estimated by \(E\{E(Y_i \vert D_i = 0, X_i) \vert D_i = 1\}\) and the treatment effect can be estimated by \(E(Y_i \vert D_i = 1) - E\{E(Y_i \vert D_i = 0, X_i) \vert D_i = 1\}\).

Answer:

\(\begin{aligned} E\left[Y_i(0) \mid D_i=1\right] & =E\left\{E\left[Y_i(0) \mid X_i, D_i=1\right] \mid D_i=1\right\} \\ & =E\left\{E\left[Y_i(0) \mid X_i, D_i=0\right] \mid D_i=1\right\}, \text { conditional independence } \\ & =E\left\{E\left(Y_i \mid X_i, D_i=0\right) \mid D_i=1\right\} \end{aligned}\).

So the counterfactual can be measured by the data. As a result, \(\begin{aligned} \tau_{\text {treat }} & =E\left[Y_i(1) \mid D_i=1\right]-E\left[Y_i(0) \mid D_i=1\right] \\ & =E\left[Y_i(1) \mid D_i=1\right]-E\left\{E\left(Y_i \mid X_i, D_i=0\right) \mid D_i=1\right\}, \end{aligned}\).

which can also be measured by the data.

The basic idea here is you can change \(Y_i\) conditional on \(D_i\), and you can change \(D_i\) conditional on \(X_i\). So the counterfactual can be measured by the data.

2. We then we can estimate \(E(Y_i(0) \vert X_i)\).

by conditional independence:

\(E\left(Y_i(0) \mid X_i\right)=E\left(Y_i(0) \mid D_i=0, X_i\right)=E\left(Y_i \mid D_i=0, X_i\right)=\alpha+\beta X_i\).

So we may represent \(Y_i\) as \(Y_i=\alpha+\beta X_i+u_i, E\left(u_i \mid D_i=0, X_i\right)=0\).

The basic idea here is to estimate parameters, we need make \(Y_i\) rather than \(Y_i(0)\) as the dependent variable.

3. Provide a consistent estimator for the counterfactual \(E[Y_i(0) \vert D_i = 1]\).

Answer:

\(\begin{aligned} E\left[Y_i(0) \mid D_i=1\right] & =E\left\{E\left(Y_i \mid X_i, D_i=0\right) \mid D_i=1\right\} \\ & =E\left[\alpha+\beta X_i \mid D_i=1\right] \\ & =\alpha+\beta E\left(X_i \mid D_i=1\right) \end{aligned}\).

Then, a consistent estimator for the counterfactual is given by \(\hat{\alpha}+\hat{\beta} \bar{X}^{(1)}\).

**4. ** Provide a consistent estimator for the treatment effect \(E[Y_i(1) \vert D_i = 1] - E[Y_i(0) \vert D_i = 1]\).

Answer:

Based on we have, we can conclude it can be estimated by \(\hat{\tau}_{\text {treat }}=\bar{Y}^{(1)}-\left(\hat{\alpha}+\hat{\beta} \bar{X}^{(1)}\right)\).

5. Full Sample estimation: \(\begin{aligned} E\left(Y_i \mid D_i, X_i\right) & =E\left(Y_i(0) \mid D_i, X_i\right)+E\left(Y_i(1)-Y_i(0) \mid D_i, X_i\right) D_i \\ & =E\left(Y_i(0) \mid X_i\right)+E\left(Y_i(1)-Y_i(0) \mid X_i\right) D_i, \text { by conditional independence } \\ & =\alpha+\beta X_i+\rho D_i \end{aligned}\).

As a result, we may form a regression model \(Y_i=\alpha+\beta X_i+\rho D_i+v_i, E\left(v_i \mid D_i, X_i\right)=0\).

The coefficients \((\alpha, \beta, \rho)\) can be unbiasedly and consistently estimated by OLS regression of \(Y\) on \(X\) and \(D\) for the full sample.

Topic 2: Finite Sample Thoery of OLS

If we want to transform linear regression into a causal inference problem, we need to make sure the following assumptions hold.

Assumption

Assumption 1(model linaer in parameters)

Assumption 2(full rank or no multicollinearity)

- The matrix \(X'X\) is full rank.

- Each variable cotains unique information.

Assumption 3(stict exogeneity)

- \(X_i\) is not correlated with \(\epsilon_i\).

- Mean independence assumption: \(E(\epsilon \vert X) = 0\).

- or \(E(\epsilon_i \vert X_1i, X_2i...) = 0\).

- A weaker assumption: \(E(\epsilon_i \vert X_i) = 0\).

- the conditional esentially focues on different sections of the entire population.

Assumption 4(spherical disturbance - on conditional variance/covariance)

- homoskedasticity: \(E(\epsilon_i^2 \vert X_i) = \sigma^2\) while no cross correlation between \(\epsilon_i\) and \(\epsilon_j\).

Assumption 5: normality of disturbance

- \(\epsilon_i \sim N(0, \sigma^2)\).

- useful for making statistical inference.

Algebra of OLS

- Based on first order condtion, we can have OLS estimator \(\hat{\beta} = (X'X)^{-1}X'Y\).

- The fitted value \(\hat{Y} = X\hat{\beta}\).

- The residual \(e = Y - \hat{Y}\) or in vector form: \(e = Y - X\hat{\beta} = (I - X(X'X)^{-1}X')y = M_x y\).

- the matrix M_x is called annihilator matrix, while P_X = X(X’X)^{-1}X’ is called projection matrix.

- if we multiply X by M_x, we get 0.

- since e is defined as part of y that is not linearly related to X, e is orthogonal with X: \(X'e = X'M_Xy = 0\).

- The projection leads to the predictor \(\hat{Y} = X\hat{\beta} = X(X'X)^{-1}X'Y = P_X Y\).

- By this definition, \(\hat{y}\) is orthogonal to \(e\).

- Both \(M_X\) and \(P_X\) are symmetric and idempotent.

- symmetric: \(M_X = M_X'\).

- idempotent: \(M_X^2 = M_X\).

- The normal equation \(\sum_i=1^{n}{x_i e_i} = 0\).

- matrix form: \(X'e = 0\) (\(e = My\)).

Partitioned Regression

- Let \(X = (X_1, X_2)\), \(b = (b_1, b_2)\).

- We have \(X'Xb = X'Y\).

- We can solve to get

- \(b_1 = (X_1' M_2 X_1)^{-1}X_1'Y\),

- \(b_2 = (X_2' M_1 X_2)^{-1}X_2'Y\).

- Interpretation: we partial out the effect of X_2 thus \(b_1\) is the effect of X_1 on Y.

- Orthogonal regressors: suppose X_1 and X_2 are orthogonal, then \(b_1 = (X_1'X_1)^{-1}X_1'Y\), \(b_2 = (X_2'X_2)^{-1}X_2'Y\).

R-squared

- define a one-value vector \(i = (1, 1, ..., 1)\).

- \(p^0 = i (i' i)^{-1} i' = i (1/n)^{-1} i' = 1/n\).

- \(M^0 = I - p^0 = I - 1/n\).

- \(R^2 = \frac{ESS}{TSS} = \frac{\sum_i^n{\hat{y_i} - \bar{y}}}{\sum_i^n{y_i - \bar{y}}} = 1 - \frac{e'e}{y'M^0y}\).

- \(R^2 = \frac{var(a + bx)}{Y} = 1 - \frac{var(u)}{var(Y)}\).

Statistical Properties of OLS under Finite Sample

- Unbiasedness: \(E(\hat{\beta} \vert X) = \beta\).

- \(\hat{\beta} = (X'X)^{-1}X'Y = \beta + ((X'X)^{-1}X'\epsilon)\).

- Under strict exogeneity, \(E(\epsilon \vert X) = 0\), thus \(E(\hat{\beta} \vert X) = \beta\).

- By law of interated expectations, \(E(\hat{\beta}) = E[E(\hat{\beta} \vert X)] = E[\beta] = \beta\). (unbiased)

- \(var(\hat{\beta \vert X}) = \sigma^2(X'X)^{-1}\). Under homoskedasticity.

- Variance (accuracy)

- In a simple regression model with intercept and a single regressor, \(var(\hat{\beta} \vert X) = \frac{\sigma^2}{\sum_i^n{(x_i - \bar{x})^2}}\).

- For the regression model with two random regressors, \(var(\hat{\beta} \vert X) = \frac{\sigma^2}{\sum_i^n{(x_i - \bar{x})^2}}(1 - R_{3}^2)\).

- \(R_3^2\) is the R-squared of the regression of \(X_3\) on 1 and \(X_2\).

Proof:

-

Consider the partitioned regression model \(Y = X_1b_1 + X_2b_2 + \epsilon\).

-

In a partitioned regression: \(X=\left[X_1, X_2\right], \beta=\left(\beta_1^{\prime}, \beta_2^{\prime}\right)^{\prime} \in R^{K_1+K_2}, \hat{\beta}=\left(\mathbf{b}_1^{\prime}, \mathbf{b}_2^{\prime}\right)^{\prime},\).

- and \(\mathbf{b}_2=\left(X_2^{\prime} M_1 X_2\right)^{-1} X_2^{\prime} M_1 \mathbf{y}\),

- where \(M_1=I-X_1\left(X_1^{\prime} X_1\right)^{-1} X_1^{\prime}\).

- Denote \(X=\left(X_1, x_{(K)}\right)\) in other words \(X_2=x_{(K)}\), which contains the Kth variable, then

- Thus \(\mathbf{E}\left(\mathbf{b}_2 \mid X\right)=\beta_2\) and \(\operatorname{var}\left(\mathbf{b}_2 \mid X\right)=\sigma^2\left(X_2^{\prime} M_1 X_2\right)^{-1}\)

where \(\begin{aligned} X_2^{\prime} M_1 X_2 &= x_{(K)}^{\prime}\left[I-X_1\left(X_1^{\prime} X_1\right)^{-1} X_1^{\prime}\right] x_{(K)} \\ & =\left[x_{(K)}-X_1\left(X_1^{\prime} X_1\right)^{-1} X_1^{\prime} x_{(K)}\right]^{\prime}\left(x_{(K)}-X_1\left(X_1^{\prime} X_1\right)^{-1} X_1^{\prime} x_{(K)}\right) \\ & =e'_{(K)}{e }_{(K)} \\ & =\frac{e_{(K)}^{\prime} e_{(K)}}{\sum_{i=1}^n\left(x_{i K}-\bar{x}_K\right)^2} \sum_{i=1}^n\left(x_{i K}-\bar{x}_K\right)^2 \\ & =\left(1-R_{(K)}^2\right) \sum_{i=1}^n\left(x_{i K}-\bar{x}_K\right)^2, \end{aligned}\)

where \(R_{(K)}^2\) is the R-squared of regressing \(x_{(K)}\) on \(X_1\).

- Hence \(\operatorname{var}\left(\mathbf{b}_2 \mid X\right)=\sigma^2\left(X_2^{\prime} M_1 X_2\right)^{-1}=\frac{\sigma^2}{\sum_{i=1}^n\left(x_{i K}-\bar{x}_K\right)^2} \frac{1}{\left(1-R_{(K)}^2\right)}\)

where \(R_{(K)}^2\) is the R-squared of regressing \(x_{(K)}\) on the rest of the variables.

Gaussian-Markov Theorem

Topic 3: Empirical Methods First Look

Selection Bias

Selection bias occurs when the sample is not representative of the population. We can control some variables, we hope to make treatment randomly assigned conditional on the control variables.

- We have many tools to deal with selection bias:

- control variables

- use external instruments

- randomized controlled trials

- exploit information from quasi-experiments or natural experiments

- construct a proxy control group

Ommitted Variable Bias

Omitted variable bias occurs when a variable that affects both the dependent variable and treatment effect is not included in the regression model.

Control variables Methods

- Control variables are variables that are correlated with the treatment variable but are not affected by the treatment variable.

- For a causal model:

- \(Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X + u\).

- where \(u\) includes all other causal factors that affect \(Y\) but are not included in the model.

- We want to find a regression model:

- \(Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X + \beta_2 Z + e\), \(E(e\vert X,Z) = 0\)

- such that \(\beta_1\) is unbiased.

- We achive this by using a control variable \(Z\) that conditional on \(Z\), \(u\) is independent of \(X\).

- \(E(u\vert X,Z) = E(u\vert Z)\) (Conditional Independence means Condtional mean Independence).

- We can assume the conditional mean is linear: \(E(u\vert X, Z) = E(u\vert Z) = \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 Z\).

- Then we can represent u as \(u = \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 Z + e\). \(E(e \vert X,Z) = 0\).

- The causal model becomes \(Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X + \alpha_0 + \alpha_1 Z + e\), where \(E(e\vert X,Z) = 0\).

What to control?

- A good control variable makes conditional mean independence assumption more likely to hold.

- We can control more for a robustness check.

- The coefficients of the control variables are not cessarily causal and we do not need to interpret them.

Bad controls

- Bad controls block the causal channel of interest and lead to biased estimation.

Proxy Controls

- Some controls are not available in the data. We can use proxy controls, such as the ability.

Cluster Robust Standard Errors

- We can use cluster robust standard errors to control for the correlation between observations within the same cluster.

- The clustered standard errors will take into account the correlation between observations within the same cluster.

- Conventional SE assume: \(\sigma_{i j}=\sigma^2\), if \(i=j\), and \(=0\) if \(i \neq j\). \(\operatorname{var}(u)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc} \sigma^2 & \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & \cdots & \sigma^2 \end{array}\right]\)

- Robust SE assumes: \(\sigma_{i j}=\sigma_i^2\), if \(i=j\), and \(=0\) if \(i \neq j\). \(\operatorname{var}(u)=\left[\begin{array}{ccc} \sigma_1^2 & \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & \cdots & \sigma_n^2 \end{array}\right]\)

- Cluster SE assumes: \(\sigma_{i j}=\left\{\begin{array}{cc} \sigma_i^2, & i=j \\ 0 & i, j \text { not in the same school } \\ \sigma_{i j} & i, j \text { in the same school } \end{array}\right.\)

- Suppose there are \(S\) schools. Let \(\Sigma_s\) denote covariance of errors in school s that has \(n_s\) students: \(\Sigma_s=\left[\begin{array}{ccc}\sigma_1^2 & \cdots & \sigma_{1 n_s} \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ \sigma_{n_s 1} & \cdots & \sigma_{n_s}^2\end{array}\right]\).

- Then \(\operatorname{var}(u) \equiv\left[\begin{array}{ccc} \sigma_1^2 & \cdots & \sigma_{1 n} \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ \sigma_{n 1} & \cdots & \sigma_n^2 \end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{ccc} \Sigma_1 & \cdots & 0 \\ \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & \cdots & \Sigma_S \end{array}\right] \text { is block diagonal. }\)

Instrumental Variables and Two-Stage Least Squares

- The causal model is \(Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X + u\).

- However, \(cov(X, u) \neq 0\), so we cannot use OLS to estimate the causal effect.

- The instrumental variable method is to use a variable \(Z\) that is correlated with \(X\) but not with \(u\).

- Stage 1: Regress \(X\) on \(Z\): \(X = \gamma_0 + \gamma_1 Z + v\).

- Stage 2: Regress \(Y\) on \(X\): \(Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X + u\).

When we need to use instrumental variables?

- When the treatment variable is endogenous, we need to use instrumental variables.

- Example 1: if new scientific evidence shows more adverse effects of cigarettes, it would reduce the demand and then negatively affect the price.

- \(u\) includes demand shock, which also affect price.

- In short, shocks that affect both the treatment and the outcome are called reverse causality or simultaneous causality.

- In this case, a valid instrument is the sales tax.

- Relevant: \(cov(X, Z) \neq 0\)

- Exogenous: \(cov(Z, u) = 0\), the tax does not influence the demand directly but only indrectly through price.

- In this case, a valid instrument is the sales tax.

Randomized Experiments

- The causal model: \(Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 D + u\).

- Suppose the treatment dummy is randomly assigned, then

- \(cov(D, u) = 0\).

- \(E(u \vert D) = 0\).

- \(u_i indepent of D_i\).

Panel Data

- The causal model is \(Y_{it} = \beta_0 + \alpha_i + \beta_1 X_{it} + e_{it}\).

- where \(\alpha_i\) is the time-invariant individual effect.

- Consider the time difference, we have \(Y_{it} - Y_{i, t-1} =\beta_1 X_{it} + e_{it} - \beta_1 X_{i, t-1} - e_{i, t-1}\).

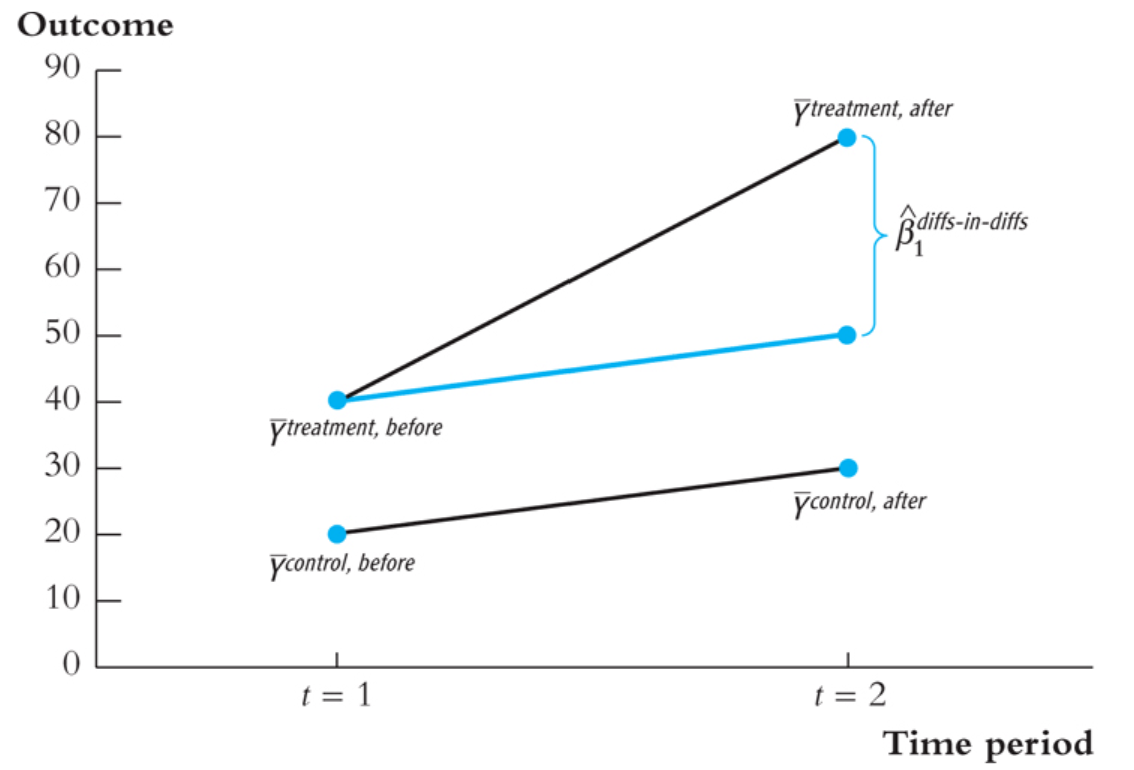

Difference-in-Difference (DID)

- Y is measured in two periods, before and after the treatment.

- Control group: \(Y_{it}^{control}, t = before, after\)

- Treatment group: \(Y_{it}^{treatment}, t = before, after\)

- Conditional Parallel Trend: \(E(Y_{it}^{treatment} - Y_{it}^{control} \vert D = 1, X_{it}) = (Y_{it}^{treatment} - Y_{it}^{control} \vert D = 0, X_{it})\).

- This means the difference between the treatment and control group should be the same before and after the treatment conditional on X.

- Regression model of DID: \(Y_{it}^{treatment} - Y_{it}^{control} = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X_{it} + e_{it}\).

- \(\beta_1\) is the effect of the treatment on the outcome conditional on the treatment.

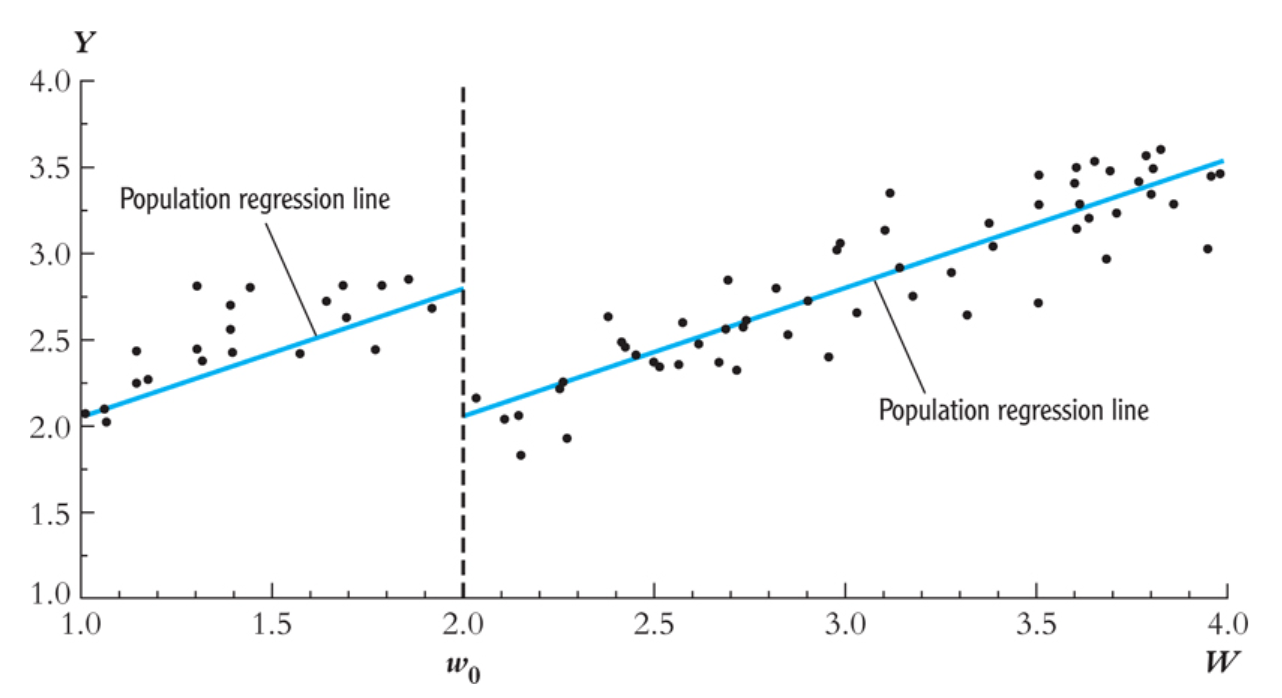

Regression discountinuity (RDD)

- The causal model is \(Y_{it} = \beta_0 + \alpha_i + \beta_1 X_{it} + e_{it}\).

- If \(X_{it}\) is a continuous variable, we can use the regression discontinuity design (RDD).

- The effect of treatment should show up as a jump in the outcome at the cutoff point.

- sharp regression: everyone above the cutoff is treated, everyone below is not treated.

- fuzzy regression: crossing the threshold influences the probability of being treated.

- Assume crossing the threshold dummy Z does not affect on \(Y\) and Z only through influencing the probability of treatment.

- Then Z is a valid instrument for treatment.

iid

- iid means that the observations are independent and identically distributed.

- However, conditional on other variables, they could be dependent.

Summary

- Potential outcomes

- causal effect (causal model)

- RCT

- regression

- Observational data

- Condtional independence

- regression with controls (OLS)

- IV

- 2 stage least squares

- LATE: local average treatment effect

- GMM: generalized method of moments

- quasi-experimental

- DID: difference-in-difference

- synthetic control

- RDD: regression discontinuity design

- DID: difference-in-difference

- panel data

- Condtional independence

Topic 4: Large Sample Theory of OLS

Asymptotic properties of OLS

- Consistency of OLS (under iid): \(\hat{\beta} = \left[\sum_{i=1}^n{x_i x'_i} \right]^{-1} \left[\sum_{i=1}^n{x_i y_i} \right] = \beta + \left[\sum_{i=1}^n{x_i x'_i} \right]^{-1} \left[\sum_{i=1}^n{x_i \epsilon_i} \right]\).

- \(S_{xx} = \sum_{i=1}^n{x_i x'_i} \rightarrow E[x_i x'_i] = \Sigma_{xx}\).

- \(S_{x\epsilon} = \sum_{i=1}^n{x_i \epsilon_i} \rightarrow E[x_i \epsilon_i] = 0\).

- Thus, \(\hat{\beta} \rightarrow \beta\).

- The validity of OLS is based on the assumption that \(E(x_i \epsilon_i) = 0\) or lack of comtemporaneous correlation.

- Asymptotic normality OLS \(\hat{\beta}\) (under i.i.d.)

- \(\sqrt{n} (\hat{\beta} - \beta) = \left[\frac{1}{n} X' X\right]^{-1} \frac{1}{\sqrt{n}} X' \epsilon\).

- \(\frac{1}{\sqrt{n}}\sum_{i=1}^n{x_i \epsilon_i} \sim N(0, S )\).

- Thus, \(\sqrt{n} (\hat{\beta} - \beta) \sim N(0, \Sigma_{xx}^{-1} S \Sigma_{xx}^{-1})\)

heteroskedasticity

- The iid assumption can be relatex to no serial correlation.

- No serial correaltion or heteroskedasticity means that \(S = \sigma^2 \Sigma_{xx} = \sigma^2 E[x_i x'_i]\).

Heteroskedasticity: GLS and White test

- Heteroskedasticity: \(var(\epsilon_i \vert x_i) = \sigma_i^2\). The variance differs across \(x_i\).

Large Sample Theory of OLS on Ommited Variable Bias

- Assume the model: \(Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X + \beta_2 Z + \epsilon, E(\epsilon \vert X, W) = 0\).

- Denote the OLS for the short regression \(Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X + \epsilon\) as \(\hat{\beta}_1\).

- Then the ommited variable bias is \(\hat{beta_1} - {\beta}_1 = cov(X, Z)/var(X) = \beta_2 \beta_{Z \vert X}\).

- \(\beta_{Z \vert X}\) is the population regression coefficient of regressing \(Z\) on \(X\).

- Assume we have a model: \(Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X + \beta_2 W_1 + \beta_3 W_2 + \epsilon, E(\epsilon \vert X, W_1, W_2) = 0\). and \(W_2\) is unobservable.

- Then the OVB for regression without controls is \(\hat{\beta}_1 - \beta_1 = cov(X, \beta_2 W_2 + \beta_3 W_2) / var(X) = \beta_2 \beta_{W_1 \vert X} + \beta_3 \vert beta_{W_2 \vert X}\).

- Considering controlling for \(W_1\) but not \(W_2\), the regression is \(Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 X + \beta_2 W_1 + \epsilon, cov(u, X) = cov(u, W_1) = 0\).

- Let \(W=\left[1, W_1\right]\), then \(M_W c=0\) and \(M_W W_1=0\). the OLS

- Consider the population projection (regress both \(\mathrm{X}\) and \(\mathrm{W}_2\) on \(\mathrm{W}\) ):

- In the limit, we have:

- Remark: for a general linear regression \(y=X \beta+\varepsilon\) with \(\hat{e}\) being the OLS residuals,

- So the OVB in the limit

\(\hat{b}_1-\beta \stackrel{p}{\rightarrow} \gamma_2 \frac{\operatorname{cov}\left(e_{X}, e_2\right)}{\operatorname{var}\left(e_X\right)}\)

- the \(cov(e_X, e_2)\) is the regression coefficient of \(W_2\) on \(X\) and \(W\), so \(\beta_{W_2 \vert X, W_1} = \frac{\operatorname{cov}\left(e_{X}, e_2\right)}{\operatorname{var}\left(e_X\right)}\).

- Remark: if \(E(W_2 \vert W_1, X) = E(W_2 \vert W_1)\), then \(\beta_{W_2 \vert X, W_1} = 0\). We hope that conditional on \(W_1\), \(X\) is uncorrelated with \(W_2\).

Topic 5: Instrumental Variables

IV Estimator: the main idea is to extract exogenous variation in \(X\) to estimate the causal effect of \(X\) on \(Y\).

Endogenous Treatment

The causal model implies a linear regression model:

\[Y = \beta_0 + \beta_1 D + u\]- If we have RCT assignment of D, making it independent of \(Y\). We may get \(\beta_1 = E(Y \vert D = 1) - E(Y \vert D = 0)\).

- Then \(u = Y(0) - E(Y(0)) + (Y(1) - Y(0) - \beta_1)D\).

- The conditional mean of the causal error is \(E(u \vert D) = E(Y(0) - E(Y(0)) + (Y(1) - Y(0) - \beta_1)D \vert D)\).

- With RCT, we may get \(E(Y(0) - E(Y(0)) \vert D) = 0\), so \(E(u \vert D) = (Y(1) - Y(0) - \beta_1)D\).

Two-stage Least Squares

- The first stage is to regress \(X\) on \(Z\), and get the fitted value \(\hat{X}\).

- Then regress \(Y\) on \(\hat{X}\), and get the IV estimator \(\hat{\beta}_{IV}\).

For the first stage, there are a few assumptions:

- Linearity: \(y_i = \delta x_i + \epsilon_i\), where \(x_i\) is an L-dimensional vectors of regressors, $\delta$ is an L-dimensional vector of coefficients, and \(\epsilon_i\) is an error term.

- Ergodic stationarity.

- Orthogonality condition: let $z_i$ be a K-dimensional vector of instrument. \(E(\epsilon_i z_i) = 0\) or \(E(g_i) = 0\), where \(g_i = z_i \epsilon_i\).

- Rank condition: \(E(x_i z_i^{\prime})\) is positive definite. \(K\) should be larger than \(L\).

- Asymptotic normality. \(g_i\) is a martingale difference sequence. \(E(\epsilon_i \vert \epsilon_{i-1}, \epsilon_{i-2}, ... x_i, ...., x_1) = 0\). Then \(S = Var(\sqrt{n},\hat{g})\).

GMM

We introduce a few notations for GMM: \(\mathbf{g}_n(\tilde{\boldsymbol{\delta}}) \equiv \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \mathbf{g}\left(\mathbf{w}_i, \tilde{\boldsymbol{\delta}}\right)\) be the sample analog of the moment conditions. In our case, \(\mathbf{g}_n(\tilde{\boldsymbol{\delta}})=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \mathbf{z}_i\left(y_i-\mathbf{x}_i^{\prime} \tilde{\boldsymbol{\delta}}\right) \equiv \mathbf{s}_{z y}-\mathbf{S}_{x z} \tilde{\boldsymbol{\delta}}\) where \(\mathbf{s}_{z y}=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \mathbf{z}_i y_i \text { and } \mathbf{S}_{x z}=\frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n \mathbf{x}_i \mathbf{z}_i^{\prime}\)

Method of monents

When $K=L, Thus, we can use the condition of \(g_n = 0\) to get: \(\mathbf{s}_{z y}=\mathbf{S}_{x z} \tilde{\boldsymbol{\delta}}\)

However, when \(K>L\), we cannot solve the equation, instead, we minimizes the distance between \(\mathbf{g}_n(\tilde{\boldsymbol{\delta}})\) and \(\mathbf{0}\).

Let \(\widehat{\mathbf{W}}\) be a \(K \times K\) matrix and suppose \(\widehat{\mathbf{W}} \rightarrow_p \mathbf{W}>0\), i.e., \(\mathbf{W}\) is symmetric positive definite. \(\hat{\boldsymbol{\delta}}(\widehat{\mathbf{W}}) \equiv \arg \min _{\tilde{\delta}} J(\tilde{\boldsymbol{\delta}}, \widehat{\mathbf{W}}) \equiv \arg \min _{\tilde{\delta}} n \mathbf{g}_n(\tilde{\boldsymbol{\delta}})^{\prime} \widehat{\mathbf{W}} \mathbf{g}_n(\tilde{\boldsymbol{\delta}})\)

In our case, \(J(\tilde{\boldsymbol{\delta}}, \widehat{\mathbf{W}})=n\left(\mathbf{s}_{\mathbf{z y}}-\mathbf{S}_{\mathbf{x z}} \tilde{\boldsymbol{\delta}}\right)^{\prime} \widehat{\mathbf{W}}\left(\mathbf{s}_{\mathbf{z y}}-\mathbf{S}_{\mathbf{x z}} \tilde{\boldsymbol{\delta}}\right)\)

The F.O.C. is \(\mathbf{S}_{\mathrm{xz}}^{\prime} \widehat{W} \mathbf{s}_{\mathrm{xy}}=\mathbf{S}_{\mathrm{xz}}{ }^{\prime} \widehat{\mathbf{W}} \mathbf{S}_{\mathrm{xz}} \tilde{\delta}\)

The GMM estimator is \(\hat{\delta}(\widehat{\mathbf{W}})=\left(\mathbf{S}_{\mathbf{x z}}{ }^{\prime} \widehat{\mathbf{W}} \mathbf{S}_{\mathbf{x z}}\right)^{-1} \mathbf{S}_{\mathbf{x z}}{ }^{\prime} \widehat{\mathbf{W}} \mathbf{s}_{\mathbf{z y}}\)

Topic 7: GMM

The basic regression model is \(y_{i}=\mathbf{x}_{i}^{\prime} \boldsymbol{\delta}+u_{i}\)

To estimate the real causal effect, we need to introduce external intrumental variable \(z_i\), which is independent of \(u_i\), but may affect \(y_i\) through \(x_i\).

\[E(z_i u_i) = 0\]- In the GMM model, we define \(g_i = z_i u_i\), and the moment condition is \(E(g_i) = 0\).

- We also define \(S = E(g_i g_i^{\prime})\), and \(\hat{S} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n g_i g_i^{\prime}\).

The we have the estimator:

\[\hat{\delta} = arg min_{\delta} \hat{g}_n(\delta)^{\prime} \hat{S}^{-1} \hat{g}_n(\delta)\]The relationship between GMM and OLS, IV, 2SLS

- If \(x_i = z_i\), then \(\hat{\delta}_{OLS} = \hat{\delta}_{GMM}(w)\).

- IV: \(L = K\) and \(z^{\prime} x\) is invertible. Then \(\hat{\delta}_{IV} = \hat{\delta}_{GMM}(w)\).

- When \(L < K\), let \(\hat{W} = \hat{S}^{-1}\). Then \(\hat{\delta}_{2SLS} = \hat{\delta}_{GMM}(\hat{W})\).

- Efficient GMM: \(\hat{W} = S^{-1}\); Assume \(E(\epsilon_i^2 \vert z_i) = \sigma^2\), then \(\hat{W} = \hat{S}^{-1} = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^n z_i z_i^{\prime}\).

- \(S = E(g_i g_i^{\prime}) = E(z_i u_i u_i z_i^{\prime}) = E(z_i^2) E(u_i^2) = E(z_i^2) \sigma^2\).

- The optimal weighting in Efficient GMM is \(\hat{W} = \frac{1}{\sigma^2} E(z_i^2)\).

- \(\hat{\delta}_{2SLS} = ( x^{\prime} z (z^{\prime} z)^{-1} z^{\prime} x)^{-1} x^{\prime} (z^{\prime} z)^{-1} z^{\prime} y = (x^{\prime} P_x x)^{-1} (x^\prime P_x y)\).

- when L = K, the weighting will be cancelled out. Here we can not cancel out the weighting matrix.

In sum, \(w = S^{-1}\) is the optimal weighting matrix in GMM. W is irrelevant when \(K = L\).

- Asympototic Variance

- \[S=\operatorname{Var}(\sqrt{n} \bar{g})\]

- In the estimator \(\sigma\), the variance comes from \(\hat{S}\), which is the sample variance of \(\hat{g}_n\).

- Therefore, \(\operatorname{Avar}(\hat{\boldsymbol{\delta}(\widehat{\mathbf{W}}})) \equiv\left(\mathbf{S}_{\mathbf{x z}}^{\prime} \widehat{\mathbf{W}} \mathbf{S}_{\mathbf{x z}}\right)^{-1} \mathbf{S}_{\mathbf{x z}}^{\prime} \widehat{\mathbf{W}} \widehat{\mathbf{S}} \widehat{\mathbf{W}} \mathbf{S}_{\mathbf{x z}}\left(\mathbf{S}_{\mathbf{x z}}^{\prime} \widehat{\mathbf{W}} \mathbf{S}_{\mathbf{x z}}\right)^{-1}\).

- \(var(Ax) = A var(x) A^{\prime}\).

How to conduct Efficient GMM

- Step 1: Estimate \(\hat{S} = \sum_{i=1}^{n}(\hat{g_i} \hat{g_i}^\prime)\)

- Step 2: \(\hat{\delta{\hat{S}^{-1}} = Efficent GMM}\)

Test

- \(J(\hat{\delta(\hat{S}^{-1})}, \hat{S}^{-1}) = n \hat{g}_n(\hat{\delta})^{\prime} \hat{S}^{-1} \hat{g}_n(\hat{\delta}) \sim \chi^2(L-K)\).

- If \(K = L\), then \(J = 0\).

- \(J(\delta_0, \hat{S}^{-1}) = \chi^2_K\).

- \(\delta_0\) is the true value of \(\delta\).